Technology Policy in South Korea: Problem (1) Startups

The presidential election is coming up soon. What I'm primarily interested in is technology policy. After all, 'exports' are Korea's only way to make a living.

Korea has grown well as a Fast Follower, but we're still struggling with the next phase—becoming a First Mover. That's why I thought it would be great to discuss the structural problems of Korea's tech innovation ecosystem together with all of you, so I'm writing this post. Let's discuss it together in the comments.

Amid fierce competition for global leadership in cutting-edge technology sectors like semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and biotechnology, the technological infrastructure and human capital that we've built over decades are slowly being drained away.

We need technology policies that enable large corporations, mid-sized companies, and startups to grow. Let's examine them one by one.

According to data released in December 2024, Korea's semiconductor industry faces a triple challenge: technological leveling, talent drain, and weakening investment competitiveness. Particularly concerning is that most of the talent outflow consists of mid-career senior professionals in their 30s and 40s.

Korea's R&D Cost-Effectiveness The success or failure of engineering and technological innovation isn't simply determined by the scale of R&D budgets or the number of patent applications filed. Of course, these are very important. The essence of engineering technology lies in building an ecosystem where creative ideas generate value in the market, and that value flows back as a source of innovation. However, Korea's current technology innovation ecosystem has failed to establish this virtuous cycle structure. Talented technical personnel are flowing overseas, research outcomes aren't translating into commercialization, and venture capital isn't fulfilling its role as a true value creator.

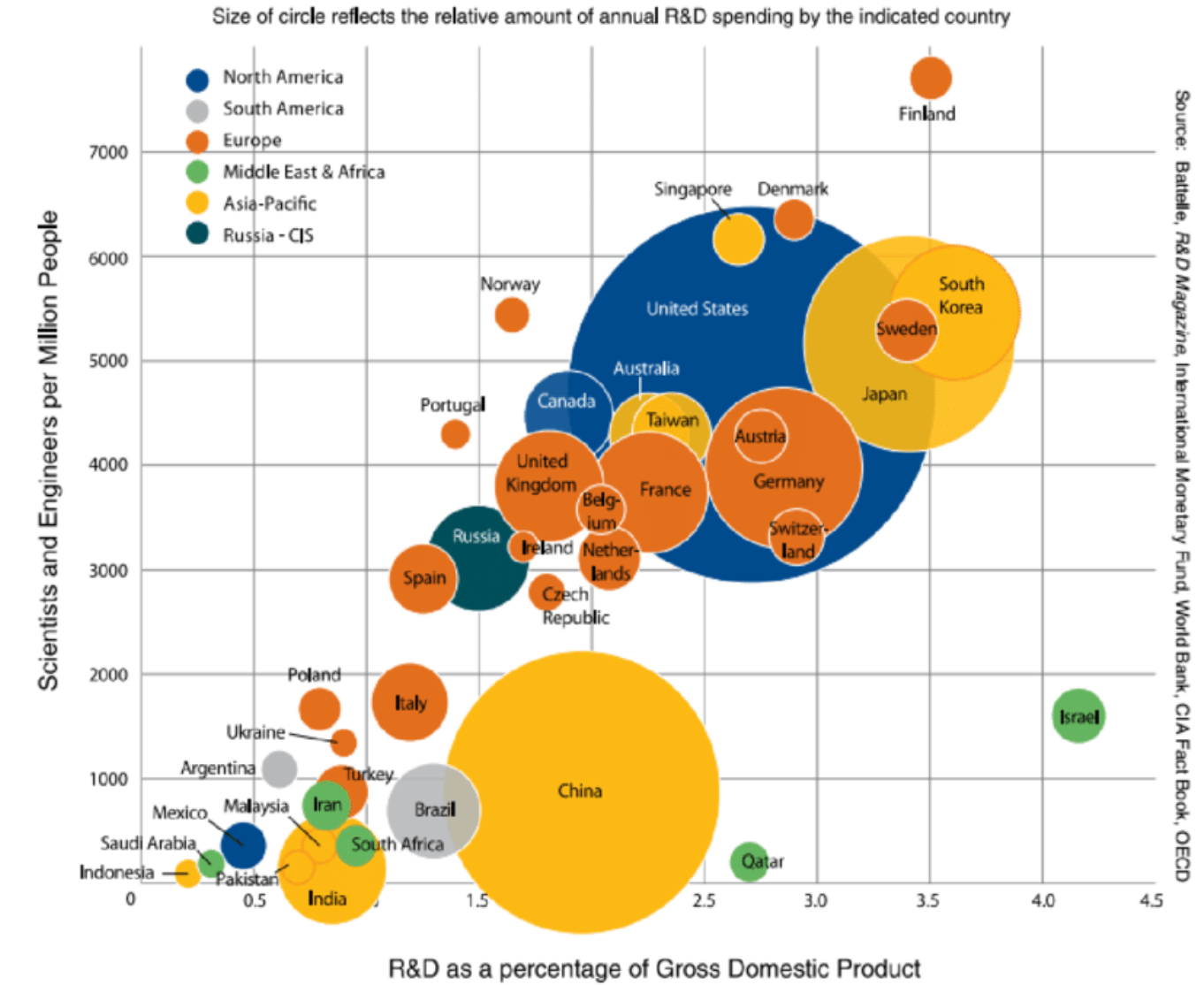

Korea's R&D budget is quite high relative to GDP. It's ranked second globally. However, there are assessments that the cost-effectiveness is the worst.

WIPO - the World Intellectual Property Organization - is one of the UN's specialized agencies that evaluates each country's innovation index annually based on patents and R&D.

The Global Innovation Index is calculated as 'Output / Investment.'

Korea ranked 6th in 2024. (Israel was outside the top 10.) Looking deeper into the data, South Korea ranks around 1st globally in human capital, but institutions and markets drag down the average.

Korea's average researcher quality is world-class at #1, yet we don't see creative output of something new or startups in new fields achieving major success in Korea.

It's hard to say this is a problem with Korean DNA, because:

- There are many cases of Koreans going abroad and succeeding with startup ventures,

- And there are also many cases where foreign "mercenaries" who were successful abroad can't make a big impact when they come to Korea.

https://innovationisrael.org.il/en/programs/yozma-fund/#about_route

According to the Korea Institute of S&T Evaluation and Planning (KISTEP)'s 2024 Global Science & Technology and ICT Policy·Technology Trend Analysis Report, major developed countries have already established virtuous cycle structures of technology-capital-talent and are focusing on creating global open innovation ecosystems.

The U.S. maintains the dynamism of its innovation ecosystem through board-centered management, substantial VC participation, systematized risk management, and unlimited growth-potential compensation structures.

Israel has established itself as a global innovation powerhouse despite its small national scale through VC ecosystem development via the Yozma Program, military-sourced technical talent supply, and global network utilization.

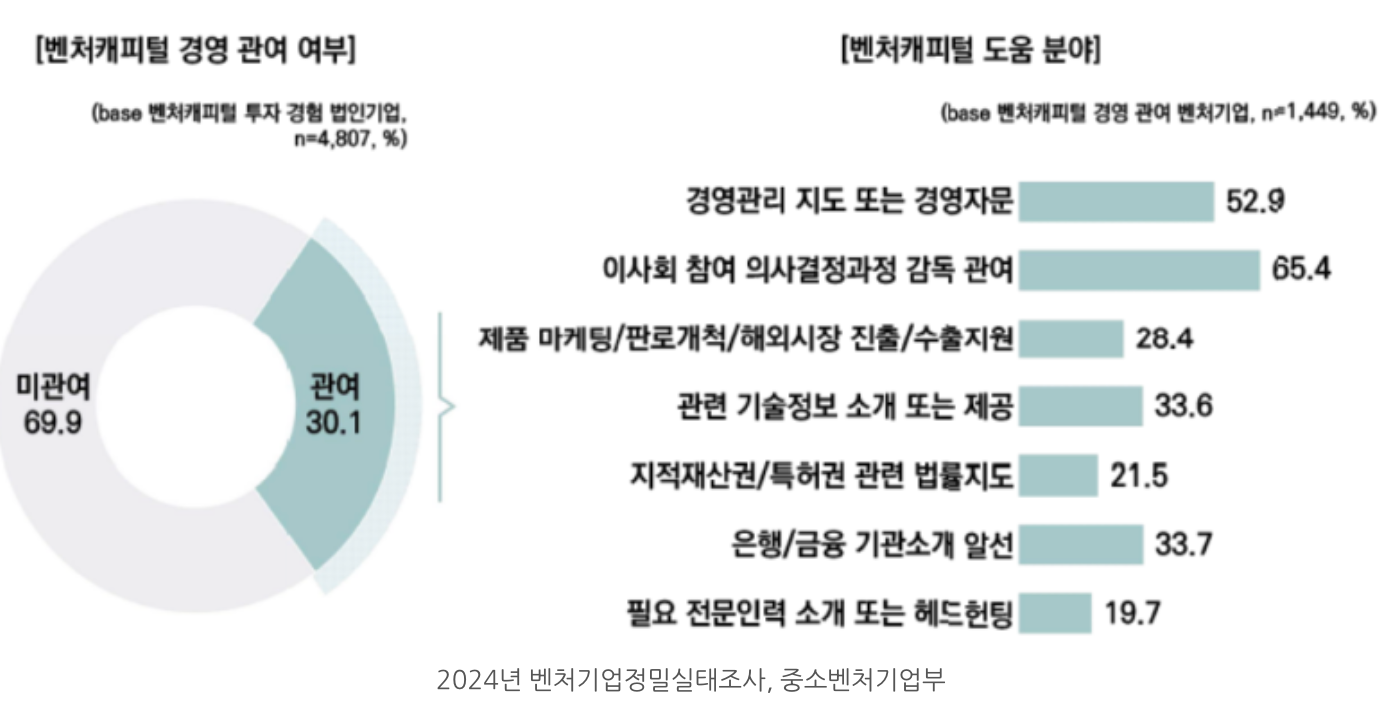

I. Structural Crisis of Korea's Technology Innovation Ecosystem Is Korean VC Just Spray and Pray? Korea's venture capital ecosystem appears vibrant on the surface, but a closer look reveals it faces serious structural limitations. According to recent surveys, a staggering 70% of companies that received VC investment reported receiving no management advice whatsoever beyond funding.

https://www.venture.or.kr/home/kor/M058765312/policy/statistics/research/index.do?idx=A

In contrast, in the U.S., 60% of VCs meet with their portfolio companies at least once a week, with 87% providing strategic advice, 72% providing investor introductions, and 69% providing customer introductions. This represents performing the role of an active partner in corporate growth, going beyond simply being a funding provider.

1. Korea's Institutional Constraints and Their Impact Restrictions on venture capital firms' management control investments make it difficult for VCs to actively participate in management. This isn't simply a matter of legal constraints, but affects the fundamental operating mechanisms of the innovation ecosystem.

In the U.S., it's common for VCs to participate on boards of directors and become deeply involved in strategic decision-making. According to research by Ewens & Malenko (2020), the average board size for U.S. startups is 4.5 members, with VCs holding approximately 2 seats, management holding 1.7 seats, and independent outside directors holding 0.8 seats.

https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/board-dynamics-over-startup-life-cycle

Professors have world-class understanding in specific technical fields, but their experience in 'investment, networking, product supply and demand, marketing, and management' is lacking compared to VCs. However, VCs have experienced many cycles of entrepreneurship and innovation, startups and failures.

The U.S. board-centered management structure creates a balance where the founder's vision, VC experience, and independent directors' expertise work together to drive corporate growth. In contrast, Korea's founder/major shareholder-centered management and formalistic board operations make it difficult to introduce professional management systems. This shifts risk for failure more to entrepreneurs than to VCs, reducing incentives for innovative but risky challenges.

2. Distorted Funding Structure Over-reliance on policy funds like Fund of Funds restricts VCs' autonomous investment decision-making. This means VC investment decisions can be excessively influenced by government policy directions.

In the U.S., pension funds serve as important LPs (Limited Partners) - essentially the "money providers" - and invest from a more long-term perspective. In particular, long-term capital such as university endowments functions as a crucial funding source for the VC ecosystem, enabling investments focused on long-term value creation rather than short-term performance.

In Korea, participation of such long-term capital is limited, and the performance evaluation methods for policy funds are concentrated on short-term indicators, hindering VCs' long-term value creation activities. Additionally, the stakeholder clauses in Fund of Funds standard contracts create contracting practices that impose excessive responsibility on entrepreneurs.

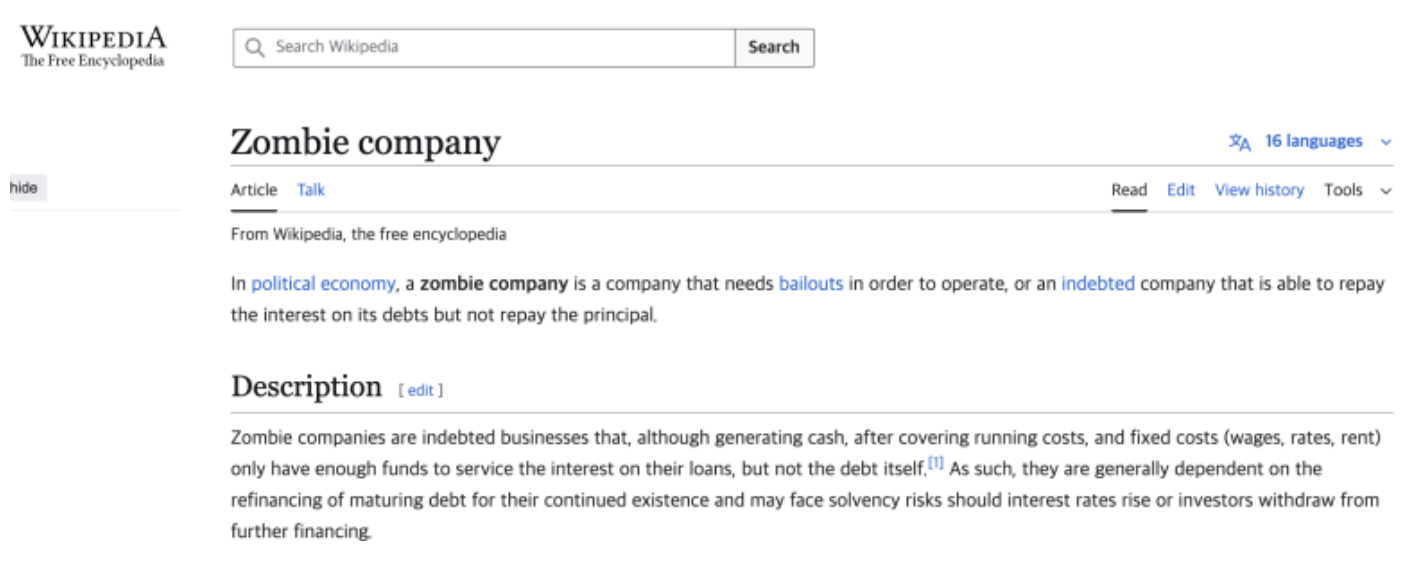

3. Absence of Failure Handling Mechanisms The structure where entrepreneurs bear liquidation costs during business closure leads to continued operation of Zombie Companies, undermining resource allocation efficiency. In Korea's startup ecosystem, rapid cleanup of failed companies and reallocation of resources are not happening smoothly.

In the U.S., VCs lead business closures and bear the costs, systematically distributing the burden of failure. This isn't simply a matter of cost burden, but contributes to forming a culture that accepts failure as a natural part of the ecosystem and learns from it.

In Korea's case, along with social stigma around failure, the costs of failure are institutionally concentrated on individuals, creating structural limitations that make it difficult for a culture of 'it's okay to fail' to take root. This acts as a major factor hindering challenging innovation.

As I'll explain below, In the U.S., it's common for engineering professors to start companies together with PhD students in their labs while conducting research at universities. (Sometimes the professor presents the idea, and sometimes the PhD student presents the idea.)

https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2019/01/26/2019012600500.html

Here's a natural English translation of the document:

Korea sees hundreds of professor startups per year, but only a handful receive investments of 5 billion won or more. (Startup investment scale has been continuously shrinking recently.)

Historically, there have been few cases of professor startups reaching IPO, but most have been in the bio field, such as Sillajen and Amicogen. (Most are from SNU and KAIST graduates.)

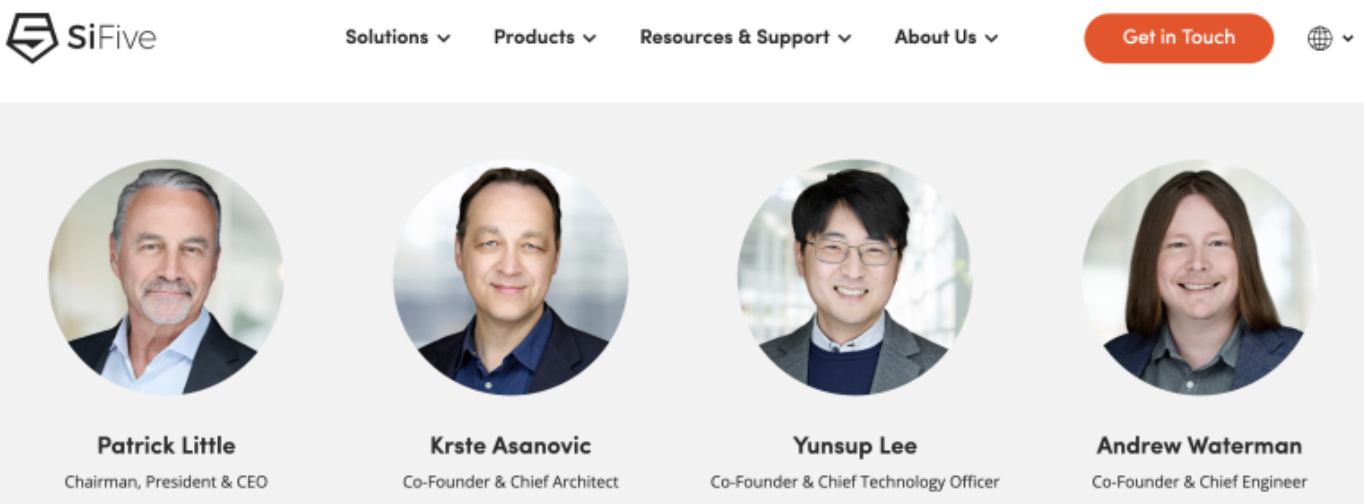

In the U.S., professor startups are led by VCs, companies are managed by boards of directors, and professors serve in key advisory roles rather than as CEOs.

They typically receive titles like Chief Architect, Fellow, Chief Scientist, or Advisor. → The costs borne by professors (founders) are their technology, time, and spare capital.

In Korea, startups are founder-led, and companies are managed around the founder. → Professors (founders) must bear the above costs plus pull in their real estate and personal credit loans.

In other words, if you don't have money to pull together, you don't even get a chance to fail. If you fail, you either become a zombie company... or have to deal with bankruptcy/rehabilitation lawyers and creditors.

4. Limitations in Expertise Accumulation

In the U.S. VC ecosystem, professionals with startup, management, and exit experience work as VCs and pass that experience to the next generation of startups.

According to research by Gompers & Mukharlyamov (2022), venture capitalists with successful founding experience (SFVC) show higher investment success rates (29.8% vs 23.2%, 19.2%) than professional VCs without founding experience (PVC) or VCs with failed founding experience (UFVC).

This suggests that just as skilled craftsmen accumulate know-how in manufacturing, VCs and serial entrepreneurs are key players in accumulating and disseminating experiential knowledge in the startup ecosystem.

However, in Korea's case, there are limited instances of successful founders or managers with exit experience transitioning to VC roles, preventing smooth accumulation and circulation of experiential knowledge within the ecosystem.

It would be great if experienced, capable VCs with good technical understanding came in to provide various consultations... but while VCs are very smart, they often lack experience.

Investment fund sizes are also decreasing recently, and for venture investment to lead to true value creation, qualitative innovation in the VC ecosystem is necessary. A role transformation is required from simple funding providers to true partners who actively support corporate growth and create value.

B. Realistic Barriers to Professor and Researcher Startups

Korea's R&D investment is among the world's highest relative to GDP, but the rate at which this investment leads to innovative company births is low.

Korea's professor startups increased from 137 in 2015 to 475 in 2023, with Korea having 4 times more professor startups per $1 billion/$1 trillion in research funding than the U.S. (as of 2021). However, according to a JoongAng Ilbo survey, 7 out of 10 professor founders regret their startups. This suggests serious qualitative problems despite quantitative growth.

1. Risk Individualization and Its Impact

In Korea, professors with technology must become CEOs and bear all risks. If the venture fails, the professor who attempted the startup must take full responsibility.

Of course, if it goes well, they take everything, and if it doesn't, they take all the risk. Nobody threatened professors with a knife to start companies. But if this situation continues, no one in Korea will be able to succeed through startups.

This individualization of risk is a major factor that makes professors hesitant to start companies. Particularly for researchers with stable professor positions, startup failure is perceived as a major risk that could negatively impact their lifelong research careers, beyond simple economic loss.

In the U.S., most professor startups don't have professors serve as CEOs but only in advisory roles, and even when they do serve as CEOs, risks are distributed.

This provides a structure where professors can focus on their specialty areas of research and technology development while participating in technology commercialization through startups.

2. Conflict of Fiduciary Duties and Institutional Limitations

When professors start companies as CEOs, there will inevitably be some interference with education and research. While there are professor concurrent position/leave systems, this creates problems of increased burden on colleague professors and infringement on students' educational rights.

National universities have somewhat more flexible standards. They can allocate one day per week to corporate activities... but restrictions exist.

Major U.S. universities generally prohibit concurrent positions as executive officers (CEO, CTO, etc.) for professor startups, allowing only advisory roles, and limit external activities (including startups) to one day per week (20%).

Using SiFive as an example: Their main products are RISC-V related products. RISC-V can be seen as ARM's almost only competitor. UCB's Professor Krste Asanovic and PhD students Yunsup Lee and Andrew Waterman founded SiFive around RISC-V. Patrik, who was an SVP at Qualcomm and Xilinx, serves as CEO.

3. Scalability Constraints and Systemic Limitations

The number of startup-leave professors that one department can handle is very limited, creating fundamental limitations on the scalability of professor startups. When professors take leave for startups, securing replacement personnel to fill the gap is difficult, adding burden to department operations and student education.

These constraints keep professor startups as exceptional activities of a few leading professors, hindering widespread diffusion. In Korea's university system, professor performance evaluation is still centered on publication records, so startup activities are not properly evaluated.

4. Diversity of U.S. Professor Startup Models and Implications

MIT's Professor Robert Langer participated in founding over 40 startups but mostly served only as scientific advisor or board member, allocating only one day per week to company activities. This way, he could maintain balance between education/research and startup activities.

U.S. professor startups are broadly divided into three models:

Founder = CEO Model: Professors directly serve as CEOs, generally resigning from their professor positions.

Founder + External CEO Model: Professors recruit professional managers as CEOs while serving in technical advisory roles.

VC-Led Model: VCs lead from the beginning, recruiting CEOs and management teams while professors hold minority stakes and advisory roles only. This is the most common model.

Most successful professor startups in the U.S. follow the second and third models. This way, professors can remain faithful to their main jobs while participating in startup activities.

Korea also needs to introduce such diverse startup models and build an ecosystem where professors can participate in technology commercialization through risk-free startups.

C. Intensifying Technology Talent Outflow Crisis

Talent outflow from Korea's high-tech industries, particularly semiconductors, has reached serious levels. During 2023-2024, approximately 3,000 core personnel are estimated to have flowed overseas, with experienced professionals with over 10 years of experience comprising most of the outflow.

Talent outflow means direct loss of technological competitiveness and could lead to national security crises in the long term.

1. Fundamental Limitations of Compensation Systems

Korea's technology talent outflow stems from fundamental limitations in compensation systems:

Early Career: The U.S. provides 2-3 times higher base salaries than Korea. This gap is particularly pronounced in cutting-edge technology fields like semiconductors and AI.

- Korean semiconductor major company salary: Partially comprehensive, around 80 million won annually

- U.S. semiconductor major company salary: Comprehensive, around 150 million won annually

Late Career: Korea has a ceiling of 100 million won after tax, while the U.S. allows continuous increases. This means compensation gaps expand further as careers advance. In the U.S., there are gray-haired engineers working as Distinguished Engineers, advisors, etc. even after retirement, but this is rarely seen in Korea.

Stock Compensation Differences: The U.S. has popularized various stock compensations like ESPP (Employee Stock Purchase Plan) and RSU (Restricted Stock Unit), while Korea lacks such systems. This prevents sufficient sharing of corporate growth benefits with employees.

Currency Value: The continuous decline in won value increases the real value of dollar-based salaries, further strengthening economic incentives for overseas employment.

According to data released in December 2024, Korean semiconductor engineers moving to Chinese companies receive 3-4 times their salary plus housing and children's education support.

Why is there such a compensation difference with the U.S.? Can't Korean major companies make money?

Domestic Labor Market Rigidity: Conservative hiring and compensation systems have formed due to difficulty in layoffs. This acts as a constraint preventing companies from actively recruiting talent and providing exceptional compensation.

In the U.S., layoffs are relatively free. They hire with high salaries when needed and lay off during contraction periods. U.S. Big Tech's average tenure is much shorter than Korea's, and stability is lower. Yet applicants flock there because compensation is high and it helps careers.

Performance Evaluation Systems: Continuing from above... in Korea, even good performance brings small rewards, and poor performance still allows continued employment.

Working Hour Regulations: Rigid application of the 52-hour work week reduces R&D flexibility. Particularly in R&D fields where creative thinking and immersion are important, rigid working hour regulations can hinder this.

I have more to say about working hour regulations.

Working Hour Regulations

Amid China's growth, U.S. containment, and global supply chain regulations, we're witnessing the collapse of technological gaps we maintained until a few years ago. In advanced process fabs, stopping one line for just one minute can evaporate hundreds of thousands or millions of won.

The problem isn't 'how long to work daily' but 'how quickly to respond to crisis situations.'

The following problem frequently occurs in semiconductor operations:

(1) Machine work takes 12 hours to complete. (2) Starting work at 8 AM means completion at 8 PM. (3) Analyzing results for 2 hours from 8 PM reaches 10 PM. Start machine work at 10 PM. (4) Analyze work results at 10 AM the next day. Repeat...

This way, just Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday fills the maximum overtime hours of 12 hours. Then, for Thursday/Friday/Saturday/Sunday, no overtime is allowed, so:

(A) Hand over current work to someone else, or (B) Work overtime 'for free' [engineers usually choose this], or (C) Project schedules are affected.

Can you say "let's postpone the tape-out schedule because we've used all 52 hours this week" when discovering DRC violations 4 days before tape-out? Who will take responsibility for the delayed time-to-market and lost market share?

If there's a firefighter contracted for only 8 hours daily, they'll only fight fires for 8 hours. But if the fire doesn't go out, fighting fire for 8 hours becomes meaningless. While systems to prevent house fires are important, when fires break out, they must be extinguished first.

Ideally, there should be people volunteering to fight fires, and for people to volunteer to fight fires, appropriate compensation must be combined.

U.S. major companies don't give OT pay to engineers participating in important projects, but compensate with exceptional RSUs and promotions. (One engineer I saw participated in an important project and got promoted 3 times in 2 years. I don't know how much RSU they received.)

This includes clear project deadline setting, refresh vacations after completion, health monitoring systems, and above all, sharing the recognition that 'this is an exception, not routine.'

![[STA] Synchronous Clocks vs. Asynchronous Clocks](https://images.unsplash.com/photo-1533749047139-189de3cf06d3?crop=entropy&cs=tinysrgb&fit=max&fm=jpg&ixid=M3wxMTc3M3wwfDF8c2VhcmNofDF8fGNsb2NrfGVufDB8fHx8MTc1NTQzMzg1OHww&ixlib=rb-4.1.0&q=80&w=600)